In March of ’03, I was given the task of *exploring more than a dozen towns and cities in the central Chinese province of Hubei. I have already written briefly about

my eye-opening time in Wuhan, the capital and largest city of Hubei, and now infamous because of the Wuhan Flu (COVID-19). This was just the beginning of a wonderful season in my early missionary life (only the second full month I spent in China), but was not without many challenges and surprises. What follows is my attempt, seventeen years later, to put down on paper some of the most interesting experiences from that particular month of travel, most of which I have only ever shared orally down through the years.

*Our “explorations” were fact-finding and planning missions in advance of future evangelistic teams. We were kind of like Joshua’s spies, scouting out the “promised land”.

Sneaky in Xiangfan

We were expressly told by our leaders not to be so overly zealous in our personal evangelism that we got into trouble and put at risk the future missions trips that were being planned in these target regions. However, a few of us struggled with these orders. Indeed, it was hard not to want to do something – ANYTHING! – to reach the millions of unevangelized Chinese I encountered traveling around the countryside on trains and buses, and on foot in the never-ending expanse of streets and alleys. But it was also impractical to carry enough Bibles and tracts in my backpack to last more than just a very short time. I was to be in Hubei for about a month, so I loaded up as many Chinese tracts and New Testaments as I could fit in my bag, knowing I would have to make due for the duration of my time there.

So I resisted the riskier methods of tract distrubution usually reserved for short-term teams (sneaking out at night and canvassing large portions of a city), and instead went about my evangelistic duties in a more subtle, refined way. I would discreetly leave tracts in shops and restaurants, where they were likely be found, but not until some time later, or at least until I was out the door and in a different part of town. I would also give New Testaments to local restaurant workers after chatting with them over bowls of hand-made noodles. These methods had the advantage of reaching many people with the truth of God’s Word without drawing too much attention to myself, and without running out of materials too quickly.

So I resisted the riskier methods of tract distrubution usually reserved for short-term teams (sneaking out at night and canvassing large portions of a city), and instead went about my evangelistic duties in a more subtle, refined way. I would discreetly leave tracts in shops and restaurants, where they were likely be found, but not until some time later, or at least until I was out the door and in a different part of town. I would also give New Testaments to local restaurant workers after chatting with them over bowls of hand-made noodles. These methods had the advantage of reaching many people with the truth of God’s Word without drawing too much attention to myself, and without running out of materials too quickly.

All was going swell until my first full day exploring the city of Xiangfan on foot. Xiangfan, whose name was changed to Xiangyang in 2010, is a large city a few hours (200 miles) northwest of Wuhan. I remember walking along a large avenue for miles, heading in a southwesterly direction from the train station on the north side of the city. I eventually came to a *Xinhua bookstore, a government bookshop found in every town and city in China, and I went in to have a look around.

While browsing the books, most of which were very boring, I tried to discreetly place tracts inside each one before putting them back on the shelf. This went on for quite some time, and I was probably getting a bit careless with my sleight-of-hand skills. I was not yet familiar with a peculiar custom of Chinese retail, that of hiring way more workers than is really necessary just to “keep an eye on things”. So while I assumed I was being nice and sly, there was evidently at least one bored worker who was keeping a pretty keen eye on me throughout most of my book browsing.

I can’t remember how many tracts I had placed in books, when my cover was blown. Suddenly, I was approached by a worker with a tract in her hand (which she must have removed from one of the books). I looked at her innocently (“Who me?”) and played dumb just long enough to excuse myself (in sign language) and make for the door. Once out on the sidewalk, I was able to escape any further interrogation by quickly putting a few blocks distance between myself and the bookshop.

*Xinhua used to be the only official bookstore in China, and is still by far the most common one. It is very much a tool of the Communist Party. All of the books permitted to be sold there are approved by Party censors. For instance, the only “Bible” to be found in these bookstores is a book of “Bible fables” for kids, which present biblical truth in a similar way as ancient Chinese or Greek mythology. By far the best use of these bookstores, other than placing tracts all about, is to purchase maps! All kinds of maps are available, from massive ones showing all of China, to detailed atlases broken down by province. We have put these government maps to great use over the years as we have targeted unreached places all throughout western China.

Mah-ding Lu-dah

So somehow I found myself attempting to play billiards in a smoky, underground pool hall a few blocks away from my cheap hotel (you’re read more about this special hotel in a later story). I started out by myself, but at some point a young Chinese guy (he was probably around 30, which seemed OLD to my 19 year-old self) joined me. I can’t remember for sure, but I think his name was Mark (although I wouldn’t bet any more on that than I would bet on a game of pool).

I might not be able to remember his name for sure, but I do remember the first thing he tried to say to me in broken English:

“You know… Mah-ding Lu-dah?”

I know who?

“Mah-deeng Loo-dah!” (makes the sign of a cross)

Martin Luther? No, I don’t know him.

I mean, YES, I DO know who Martin Luther is!

“Yes, yes! Ma-ting Lu-dah! Ma-ting Lu-dah!”

I do not remember much more of our dialogue, which eventually switched to Mandarin (he spoke English to me first, assuming that I didn’t speak much Chinese), but it turns out he was a Christian and was trying to ask me if I was a Christian too! He had come to believe in Jesus in college a few years earlier after hearing the Gospel from his American teacher, whose name was Peter. (Wow, how do I remember that?! Maybe because the way he said it was kind of like “Loo-dah”: “Pee-dah”)

So Mark and I hung out a bit more that night, and then even took a day trip together later that week to visit another nearby city on my “explore” list. Unfortunately, I don’t remember much else from our conversations and we lost contact with one another soon after. You must remember, this was back before I even owned a cell phone. But I’ll never forget the day a Chinese Christian reached out to me for fellowship by asking if I knew who “Mah-ding Lu-dah” was!

Kung Fu Bar Fight

Speaking of hanging out in pool halls and bars, I had another unique experience right in that same part of town. It might have even been the same night I met Mark, as I walked back to my hotel. I don’t know how it started, but I got to see a real live-action fight between a couple of Chinese guys who had been drinking at a bar (or possibly a pool hall).

Now you have surely seen a kung fu or Chinese martial arts movie of some kind. Jet Li, anyone? Jackie Chan? So you must have assumed (as I did) that witnessing a fight in China might be something really special; that the average Chinese dude likely grows up learning kung fu like Americans learn to play tee ball or dodge ball. The Kung Fu Panda movies and “The Karate Kid” have all come out since I first got to China, reinforcing even more the way we think and what we assume about Chinese street fighters.

But let me tell you, I was shocked at what I saw. First, I heard a commotion of some sort on the other side of the little park. Then a guy pops out of a stairwell that led to an underground joint of some sort, probably a bar. He looked terrified, and immediately took off running as fast as he could. Then another guy came careening up the same stairway and out into the park, with a broken beer bottle in his outstretched hand, screaming and cursing at the top of his lungs and chasing the first guy down the street at full speed.

I just stood there watching. My first instinct was to protect the first guy, if he got caught by the second guy with the broken glass bottle in his hand. But there was no need to worry about that. Out of fear, or guilt, or whatever, he was MOVING and wasn’t about to get caught from behind. So my *first fight in China wasn’t really much of a fight at all, but if they had actually come to blows out in the park (maybe they had already been fighting inside the bar, how else did the bottle get broken?) it definitely would not have been like a scene from your favorite kung fu movie! In fact, the little I saw reminded me more of a good old Wild West brawl (a la “A Boy Named Sue”, by Johnnie Cash).

*Technically it wasn’t the first. A month or two earlier a teammate and I had broken up a domestic dispute between a couple of young “lovers” on a side street in the city of Fuzhou, which unfortunately, is a fairly common occurence in China.

How to Lose Your Passport

I haven’t always been one to save money (although my wife has a hard time believing me). As a kid, my mom complained that any cash I received would burn a hole in my pocket. I HAD to spend it almost immediately. Somewhere in my teenage years (probably around the time I started to EARN my own money), that changed. So when money was tight during my first year in China, I sometimes spent weeks pinching pennies (or, “mao”, as they are called in Chinese) even while traveling almost non-stop. The time that I spent traveling alone in Hubei Province turned out to be the leanest days for me financially during all of 2003, but this was partly my own fault.

Here’s what happened:

Arriving in Xiangfan in mid-March, I managed to find a small, inexpensive hotel that would allow me (as an American) to stay. Communist regimes are notorious for forcing hotels to have special permits to be able to lodge foreigners, which usually turns out to be more costly both for hotel AND guest. In some cities, it is nearly impossible to find somewhere affordable to stay because all of the smaller (cheaper) hotels have been threatened with large fines for receiving foreign guests. So it was no small feat to find an inexpensive place to stay.

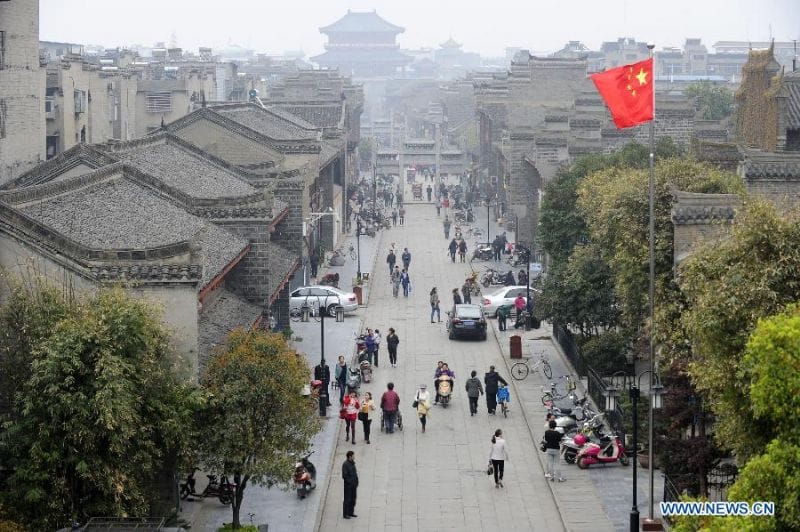

This is what Xiangfan looked like back in 2003, before the skyscraper boom took over China.

This is what Xiangfan looked like back in 2003, before the skyscraper boom took over China.

When choosing a smaller Chinese hotel, it was almost always our custom to have a look at the available rooms first, just to make sure there were no *surprises and that everything worked properly (ie, water, doors, windows). It was also customary to ask the price of each room or type of room as you were being shown around. In this case, the first room she showed me was a very small one-bed room at the end of an upstairs balcony. The room had no running water or bathroom, but neither did any of the rooms in this hotel. Those were all available in a “common” bathroom downstairs. The single room was only 15 RMB per night (just under $2 at the time), which seems extremely cheap unless you know that my target budget for those days was $3 per day total (lodging, food, transportation).

*I’ve met with countless surprises in Chinese hotel rooms over the years, the most common being leaky pipes and showers that drained all over the bathroom floor; sometimes even into the hotel room itself. Once, near the Tibetan border, where there was only one hotel available, my father and I were given a room and expressly told “not to lock your door”, because there would be no way to open it again. “Uh, ok”, we said, not sure whether to believe them or not. When we forgot and accidentally locked the door later that day, we found out that they had been telling us the truth, as we watched a Tibetan maid rappel off the roof down to our 4th floor room using a combination of rope and bedsheets tied around her waist! Yes, we almost killed a maid by ignoring (forgetting?) the command to leave our hotel room door UNLOCKED.

So when the nice lady showed me another room right next door with FOUR empty beds and told me that I could pay for just one of them for only 10 RMB ($1.25), I jumped on that bargain! (Full disclosure: the thought did run through my head that it would be better to pay an extra 75 cents to have complete privacy). The only possible downside was if other guests showed up at the hotel later in the day (or night), the rest of the beds could be sold off one by one, and I would be forced to share my room. I decided to take my chances, since up until this moment in the day the room was completely unoccupied. And it remained unoccupied (besides myself) until sometime late into the night, probably after midnight.

My memory is a bit hazy at this point, since I was sleeping so soundly, but I remember hearing the door open and seeing the light click on. I lazily rolled over and saw through squinted eyes (I didn’t have my glasses on) the owner-lady showing a young man (twenty-something?) to his bed at the far end of the room near the door. After chatting with him briefly, she left, and he quickly settled in and the light went off. I never REALLY even woke up. I just vaguely remember, as if in a dream, seeing him being let in, and then after a few minutes all was quiet and I was back asleep. Now fast forward to the next morning…

It was already light outside when I started to wake up. Before I even opened my eyes I remembered that someone had been let in late the previous night. I immediately rolled over in bed to see if the other guy was still there. I was surprised to see he was not! And as my focus moved from across the room back to my own bedside table (which was in virtually the same “line of sight”), a sickening feeling came to my stomach. My backpack, lying flat there on the little table next to my bed, did not look right. It seemed too flat, or somehow not “full” enough. I quickly reached over and patted down on the top of the backpack, and my fears were confirmed. My passport case, which was about 6 inches long and nearly an inch thick, and also contained $200, was gone from the outside pocket where I had been keeping it.

I jumped out of bed and ran out the door and down into the courtyard, hoping the man might still be on the property. He was not. I have no idea how long he had been gone, but probably not very long. There is even a possibility that I was initially “woken up” from my deep sleep when he quietly made his exit from the room just a few minutes before. I will never know. Of course hindsight is “20-20”, as they say, but my passport and my money were gone forever; and all to save a mere 75 cents!

The Aftermath

When the hotel lady found out what had happened she was very upset (on my behalf) and graciously helped in any way she could. She was the one who contacted the police who come to investigate and file a report, even though the police ended up reprimanding her for allowing me to stay at her hotel without the proper permits (which would have been impossible for her to get). Unfortunately, the police couldn’t do very much in the way of solving the actual crime. This was before China decided to install hundreds of millions of cameras at literally every intersection, alley, and business in the nation. So my passport was definitely gone, along with a big chunk of my money, and I wasn’t going to get any of it back. My only consolation was that the hotel lady made me an amazing plate of sweet and sour fish (from scratch) later that day as a way of saying sorry.

I walked through the “old city” after leaving the Xiangfan City Police Headquarters

I contacted the US Embassy in China and found out that the next step in the process was to get a police report explaining how and where the passport was lost. That turned into a multi-day ordeal. I got to ride in a police car to the main station, which was across town, and spent quite some time sitting around expansive PSB (Public Security Bureau) offices, waiting for them to take down all my info. I had to go back across town on my own a day or two later to pick up the finished report, and I remember feeling strange the entire time with the police, because so much of our work and ministry in China relied on staying away from the police and out of their “line of sight”. I don’t remember for sure, but I might have even discreetly left a few Gospel tracts around the police station. And if I didn’t, shame on me! Its not every day that you have a valid excuse to go hang out in a large Communist police station.

Sunday Lunch: Boiled Ankle

On the Sunday that I spent in Xiangfan, I walked to the nearest church that I could find. China has many “underground” churches, which really just means that a church is not registered with the government and meets in an undisclosed location. However, it is usually too risky for local believers to have foreign visitors in their churches. But China also permits a few churches (and church buildings) to exist in many larger cities, which is what I was able to find in Xiangfan. I don’t recall much of the actual service, as my Chinese was not yet at a level where I could understand more than the most basic of terms, but I clearly remember what happened when I went to lunch at the little restaurant around the corner.

As I sat at the cheap little table with thin metal legs (anyone who has eaten at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant in China will know what I’m talking about), waiting to order my food, the young man who was serving tables came over to pour me a glass of hot water. As the just-boiled water began splashing into the flimsy cup sitting on the table in front of me, the paper-thin plastic crumpled as if it was melting as the nearly boiling water poured down over the edge of the table and right onto the tender inside of my bare ankle (I was wearing strap sandals).

It burned! I sprang out of my seat and whooped in pain, as the poor kid jumped back, frightened at my reaction. I tried to reassure him, as I hopped around the small restaurant, that I was not angry. He smiled weakly. The spot where the water landed on my inner ankle immediately grew into a large blister. I hobbled back to my hotel, trying hard not to let my sandals rub the injured area. But as much as I tried to protect the blister during the day, it would pop at night as I would accidentally move around in my sleep. I had to buy first-aid supplies, gauze and alchohol, so I could disinfect it multiple times a day and keep it covered when I was out and about. As I was traveling so extensively that month, I remember having to wear socks with my sandals for weeks to try and keep the blister from getting too dirty (and infected) from the dusty streets.

Undocumented American

After my passport was stolen, it was recommended by both the US Embassy and the police that I “travel immediately to the US Consulate in Guangzhou to have a new emergency passport issued”. The problem was that I still had a number of towns on my list to visit and research! Also, my overseer (an Aussie bloke) wasn’t thrilled that I had managed to lose my passport, and encouraged me to finish the job I had come to do. So I continued my journey into western Hubei Province, but this time with only a Chinese police report and a photocopy of my (stolen) passport.

If the same thing happened today, it would be nearly impossible to travel. Back then there were still enough small hotels that would accept travelers without “proper documentation”, and buses didn’t require passports to purchase tickets, as they do in China today. However, I was still somewhat limited on the kind of hotels I could visit. My usual habit was to spend 2-3 nights in the cheapest place possible (once for as little as $1 a night!), and then “splurge” for a night at a place that cost $5-$10 so I could actually take a shower and get cleaned up. But without a passport, it was harder to find places in the slightly higher price range! And I needed decent facilities more than ever, what with trying to keep my ankle burn blister from getting infected with who-knows-what on the dusty Chinese streets.

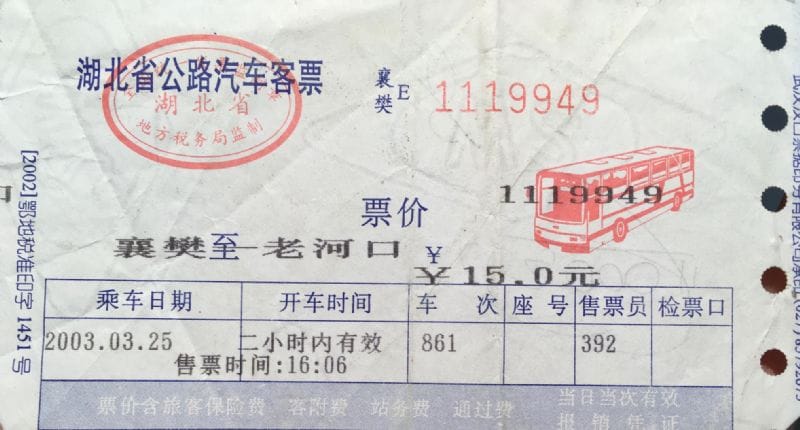

My original bus ticket from Xiangfan to Laohekou.

So I went off to visit a number of new cities with funny names like Danjiangkou and Laohekou. My only memory from either of those two cities was that I met a young man and was able to give him an English-Chinese Bible that I had recently purchased while visiting a Chinese church (possibly the one in Xiangfan, I don’t remember). From there I went on to a place called Shiyan, where I spent the night (for $2.50) in a hotel room so small that the door wouldn’t even open all the way! The double bed filled almost the entire room, yet there was a TV hanging on the wall. From Shiyan I took a bus south towards Shennongjia and the majestic Daba Mountains, which rise out of the Yangtze flood plain to a height of 10,187 ft. These rugged mountains and the large tracts of wildnerness that encompass them are a wonderful change from the never-ending towns and cities and people on the surrounding plains.

This picture has it all. Rocky peaks, pine trees, mountain villages, and the Yangtze River (lower left).

After spending a night in the small mountain town of Songbai (Cypress), my next bus continued in a southwesterly direction towards the Yangtze River. I remember staring longingly at the pine-covered mountains towering above small farmhouses and small terraced plots of recently planted crops. It seemed like corn was hanging from every rooftop and ledge, and I remember wondering to myself if it was some sort of religous ritual, similar to how the superstitious Chinese in the far south (Hong Kong, Macau, Canton) always leave small food offerings for their ancestors in little altars outside their homes and in their shops. It turns out I was wrong, for when I asked my field leader later on what all the corn could possibly mean, he smiled (smirked?) and said, “They are just hanging it out to dry!” I’ve been in China long enough now to understand exactly what they were doing with the corn. They would eventually feed it to their pigs and chickens. Turns out the Chinese in central China aren’t as religious as their neighbors to the south.

Finally arriving at the Yangtze, the bus had to drive onto a barge, a car ferry of sorts, to take us to the town of Badong, which was built on a steep slope on the south side of the river. Some of the lower parts of Badong town had already been abandoned because in the impending flooding that was to take place in the not-so-distant future, when the infamous Three Gorges Dam project was finally completed. The Yangtze was projected to rise high enough to inundate former areas of the town. This eventually happened in 2009, about six years after my visit, and recently a bridge has been built to take the place of the river ferry that I rode on so long ago.

From Badong I bused over to Enshi, where all I can remember for sure is that I made someone’s day by exchanging a $5 bill with them for some Chinese cash. I used Enshi as a base to take a short trip further west out to the remote town of Lichuan, where I was completely blown away by the towering mountain cliffs lining the valley as we bounced down the highway. I hired a taxi to take me part of the way, and the driver offered to let me take the wheel for a portion of the trip. At that point, I had never dreamed of ever driving in China (and I still wouldn’t drive for almost three years), but I was really tempted to take him up on the offer. Then I heard my dad’s voice (in my head) reminding me that China probably has rules about car insurance, liability, etc, not to mention needing a Chinese driver’s license. So I politely turned him down, and enjoyed gaping at the cliffs towering thousands of feet over my head instead!

The mountains between Enshi and Lichuan are truly incredible!

The mountains between Enshi and Lichuan are truly incredible!

Finally having explored and researched all of my allotted towns (Lichuan being the last), I bought an overnight sleeper bus ticket from Enshi back to the capital of the province, Wuhan. Turns out that the bus didn’t need all night, and we pulled into the station, also near the Yangtze River in Wuhan, well before dawn. I was still trying to save money, so I decided to take my time and just walk back to the area of town I was familiar with and the hotel where we had previously been staying. So with my large backpack weighing me down, and my ankle burn finally on the mend, I began the multi-mile trek through dark, empty streets. On one such street along a tributary of the Yangtze River, I came across a man working outside his shop, all by his lonesome. I can’t remember exactly what he was doing; it seems like he was working with metal or something. But we talked, and I attempted, in broken Chinese, to share the Gospel with him. I left him a tract. It was a natural, friendly conversation between two complete strangers from opposite corners of the world, and I will never forget it. Maybe he still talks about it as well, the night the American kid trudged by his workshop and stopped for a chat.

Here are all three of Wuhan’s districts: Wuchang (upper right), Hankou (far left), and Hanyang (foreground). My early morning walk was between Hankou and Hanyang.

Here are all three of Wuhan’s districts: Wuchang (upper right), Hankou (far left), and Hanyang (foreground). My early morning walk was between Hankou and Hanyang.

There’s nothing quite like watching a Chinese city come alive from the ground level; from the vantage point of a homeless person, or a street-sweeper. The movement starts slowly, then like critters moving around in a dark space, you start to see movement in every direction as people carry goods to market, and begin to set up fruit stalls and street-food stands. You hear a few buses start to rumble in the distance, and eventually pass by with a lone passenger or two. Finally arriving back in the neighborhood of my hotel as the city began to stir, I remembered that a yummy bowl of beef noodles would be waiting for me at the Muslim restaurant just a block or two away, and that I also needed to say goodbye to my friends there. By the time I had slurped my noodles and chatted for a bit, it was completely light outside and people were bustling about. I finally retired to the hotel to get some rest, hours after the arrival of my bus half-way across town. I had a south-bound train to catch later in the afternoon (you can see my original ticket below).

Emergency Passport

After arriving on an overnight train from Wuhan, I went straight to the US Consulate in the southern metropolis of Guangzhou early on April 1, 2003. In line, I ran into a guy who my dad had taught in college a decade or two before back in my home state of Oklahoma. Small world, indeed.

Later in the day, after paying $85 and finally receiving my new “emergency” passport, I began to scour the city for Muslim noodle shops to pass the time witnessing (and slurping home-made noodles). I was required to wait seven working days for my *Chinese Exit Visa to be processed, which would allow me to finally rejoin the rest of my team in Hong Kong.

And that would be the end of this particular story, if it wasn’t for something I just discovered in the last month…

*When you lose your passport, you also lose the visas stamped in your passport. And to exit China, you must have a valid visa. Hence, an “Exit Visa” is necessary for both visitors like me, as well as for babies who received their first passport after being born in China. We almost had to cancel an entire trip around the world one time because we forgot to apply for our son’s exit visa on time. But that’s a story for another day.

I recently stumbled upon a batch of old receipts from my first year in China. Mixed in with the random bus tickets and scribbled hotel receipts, I also found the payment stub for my emergency passport. In light of the Wuhan virus scare that has spread around the world (as of April 1, 2020), I decided to do a bit of research to see where I was during the outbreak of the infamous SARS scare of 2003. I remember being very near to Ground Zero of SARS, and I have vivid memories of checkpoints and threatened quarantines and lots of face masks (not on my own face, but everyone else) later in May and June of that year. However, when I showed up in Guangzhou way back on April 1, 2003, after a month of traversing Hubei Province, I had still never even heard of SARS yet! Yet, when I did a quick Google search the other day, I found out that the same US Consulate had evacuated all of its non-essential staff, due to the SARS outbreak, on the very day that I was there to apply for my new passport.

So what’s the point? I just find it interesting that I was there in the midst of a major outbreak, making headlines all around the world, and yet I was clueless (no wireless internet back then, folks) and safe. Sometimes the telescope (microscope?) effect of social media makes us assume that when bad or tragic things are happening in some foreign country, that the entire nation must suffering the same chaos (like a particularly disturbing scene we happen to see on our newsfeed). But this is very rarely the case. For instance, when it seemed like the whole world was talking about the epidemic that roared in Wuhan just two months ago, my own memories and personal experiences of the place were becoming obscured in my own mind by the social media hype and hysteria I was being bombarded with. It was like the world was talking about a completely different place than the one I knew. I kept having to remind myself how wonderful Wuhan can be, of what it is really like to wander through its streets, alleys, and riverside parks, and that by far the vast majority of Wuhan’s citizenry were going to be just fine.

In fact, all of the recent talk about Wuhan has made me long for the opportunity to return there once again. I have passed through a few times over the years on brief visits, but I’ve never had the leisure to explore the region again like I did the very first time back in March of ’03. Writing down so many of my early memories in China makes me long to travel freely there once more. Please pray that God would open that door for me again.

And the sooner the better!

So I resisted the riskier methods of tract distrubution usually reserved for short-term teams (sneaking out at night and canvassing large portions of a city), and instead went about my evangelistic duties in a more subtle, refined way. I would discreetly leave tracts in shops and restaurants, where they were likely be found, but not until some time later, or at least until I was out the door and in a different part of town. I would also give New Testaments to local restaurant workers after chatting with them over bowls of hand-made noodles. These methods had the advantage of reaching many people with the truth of God’s Word without drawing too much attention to myself, and without running out of materials too quickly.

So I resisted the riskier methods of tract distrubution usually reserved for short-term teams (sneaking out at night and canvassing large portions of a city), and instead went about my evangelistic duties in a more subtle, refined way. I would discreetly leave tracts in shops and restaurants, where they were likely be found, but not until some time later, or at least until I was out the door and in a different part of town. I would also give New Testaments to local restaurant workers after chatting with them over bowls of hand-made noodles. These methods had the advantage of reaching many people with the truth of God’s Word without drawing too much attention to myself, and without running out of materials too quickly.

This is what Xiangfan looked like back in 2003, before the skyscraper boom took over China.

This is what Xiangfan looked like back in 2003, before the skyscraper boom took over China. It was already light outside when I started to wake up. Before I even opened my eyes I remembered that someone had been let in late the previous night. I immediately rolled over in bed to see if the other guy was still there. I was surprised to see he was not! And as my focus moved from across the room back to my own bedside table (which was in virtually the same “line of sight”), a sickening feeling came to my stomach. My backpack, lying flat there on the little table next to my bed, did not look right. It seemed too flat, or somehow not “full” enough. I quickly reached over and patted down on the top of the backpack, and my fears were confirmed. My passport case, which was about 6 inches long and nearly an inch thick, and also contained $200, was gone from the outside pocket where I had been keeping it.

It was already light outside when I started to wake up. Before I even opened my eyes I remembered that someone had been let in late the previous night. I immediately rolled over in bed to see if the other guy was still there. I was surprised to see he was not! And as my focus moved from across the room back to my own bedside table (which was in virtually the same “line of sight”), a sickening feeling came to my stomach. My backpack, lying flat there on the little table next to my bed, did not look right. It seemed too flat, or somehow not “full” enough. I quickly reached over and patted down on the top of the backpack, and my fears were confirmed. My passport case, which was about 6 inches long and nearly an inch thick, and also contained $200, was gone from the outside pocket where I had been keeping it.

The mountains between Enshi and Lichuan are truly incredible!

The mountains between Enshi and Lichuan are truly incredible! Here are all three of Wuhan’s districts: Wuchang (upper right), Hankou (far left), and Hanyang (foreground). My early morning walk was between Hankou and Hanyang.

Here are all three of Wuhan’s districts: Wuchang (upper right), Hankou (far left), and Hanyang (foreground). My early morning walk was between Hankou and Hanyang.